“Ye who expect constancy where every thing is changing, and peace in the midst of tumult, attend to the voice of experience, and mark in time the footsteps of disappointment, or life will be lost in desultory wishes, and death arrive before the dawn of wisdom.”

So begins Mary Wollstonecraft’s unfinished story ‘The Cave of Fancy’. She wrote three chapters of it in 1787 whilst living in Bristol. Her first chapter describes a Sage who lives in a mystical cave and discovers the aftermath of a horrific shipwreck on a nearby beach. There is only one survivor: a young girl whom he decides to look after and educate. In the second chapter the Sage returns to the beach and speculates on the characters of the dead. For the third chapter a woman passing through the cave - on her way to the afterlife - tells her story of duty and love to the rescued child. Other, similar ‘educational’ chapters were planned by Wollstonecraft but never completed. She moved to London and, in 1792, published her seminal work: ‘A Vindication of the Rights of Women’. Five years later she died, just a few weeks after giving birth to her daughter Mary Shelley. Much of her work, including ‘The Cave of Fancy’, was published posthumously by her husband, William Godwin, a year after her untimely death.

I first became aware of the existence of the story when I moved to Bristol in 2016. Immediately after reading the original text, I was drawn into the idea of continuing it. Soon afterwards the project became the subject of my Graphic Arts postgrad at The University of the West of England. I would visualise Wollstonecraft’s existing narrative with photographs and evolve her unfinished story.

To begin, I started photographing in Bristol. Looking for images that might suggest the themes that Wollstonecraft had established in the book. These being: spirits & death, education & knowledge (‘Fancy’) and passage to the afterlife. It became apparent that the Avon Gorge and Leigh Woods were inspiration for much of the mystical landscape she describes. I employed a ‘drift’ approach to the photography. Very little planning, going out in all weather and at all times of day and night, no maps and always being open to chance.

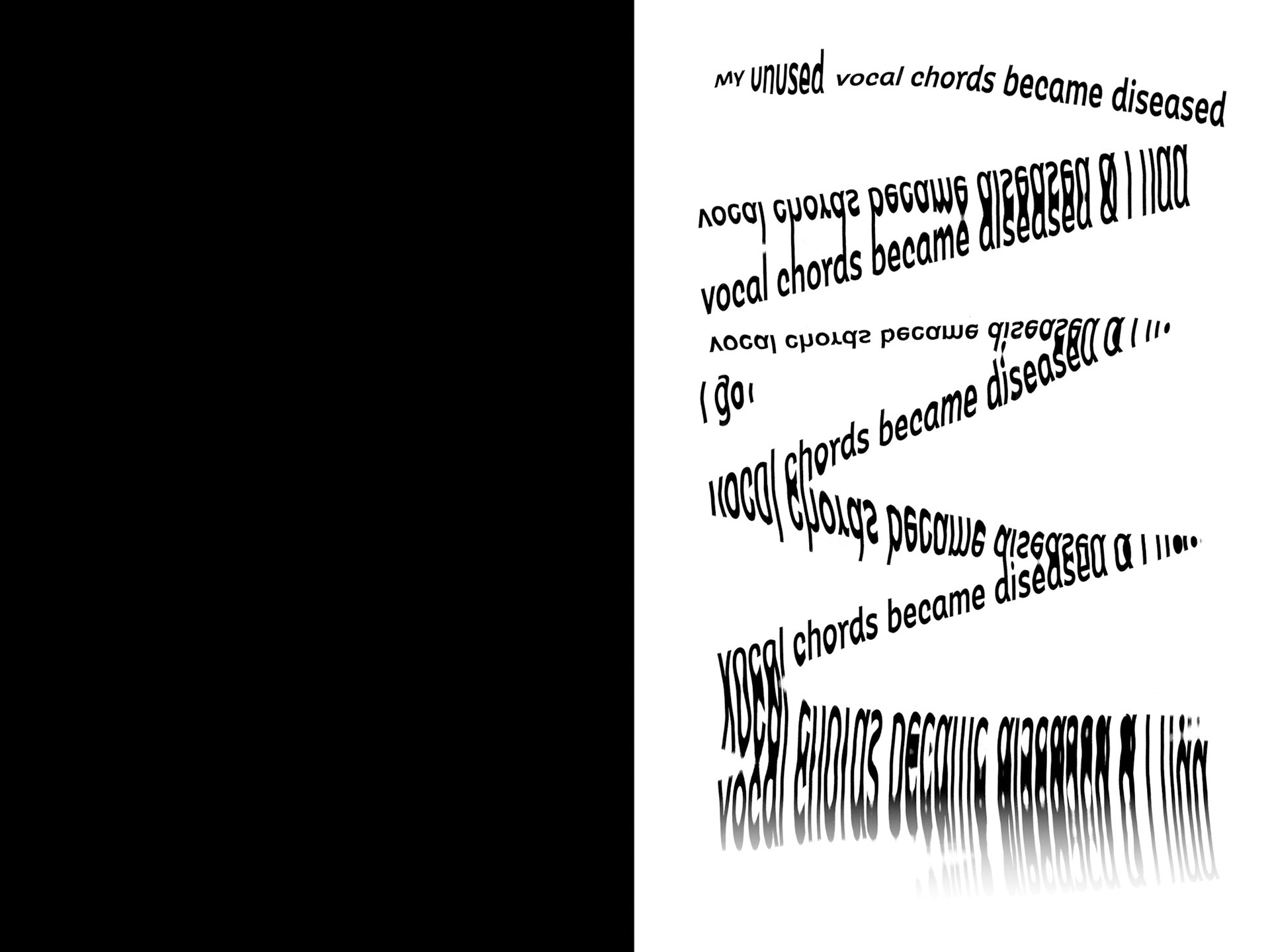

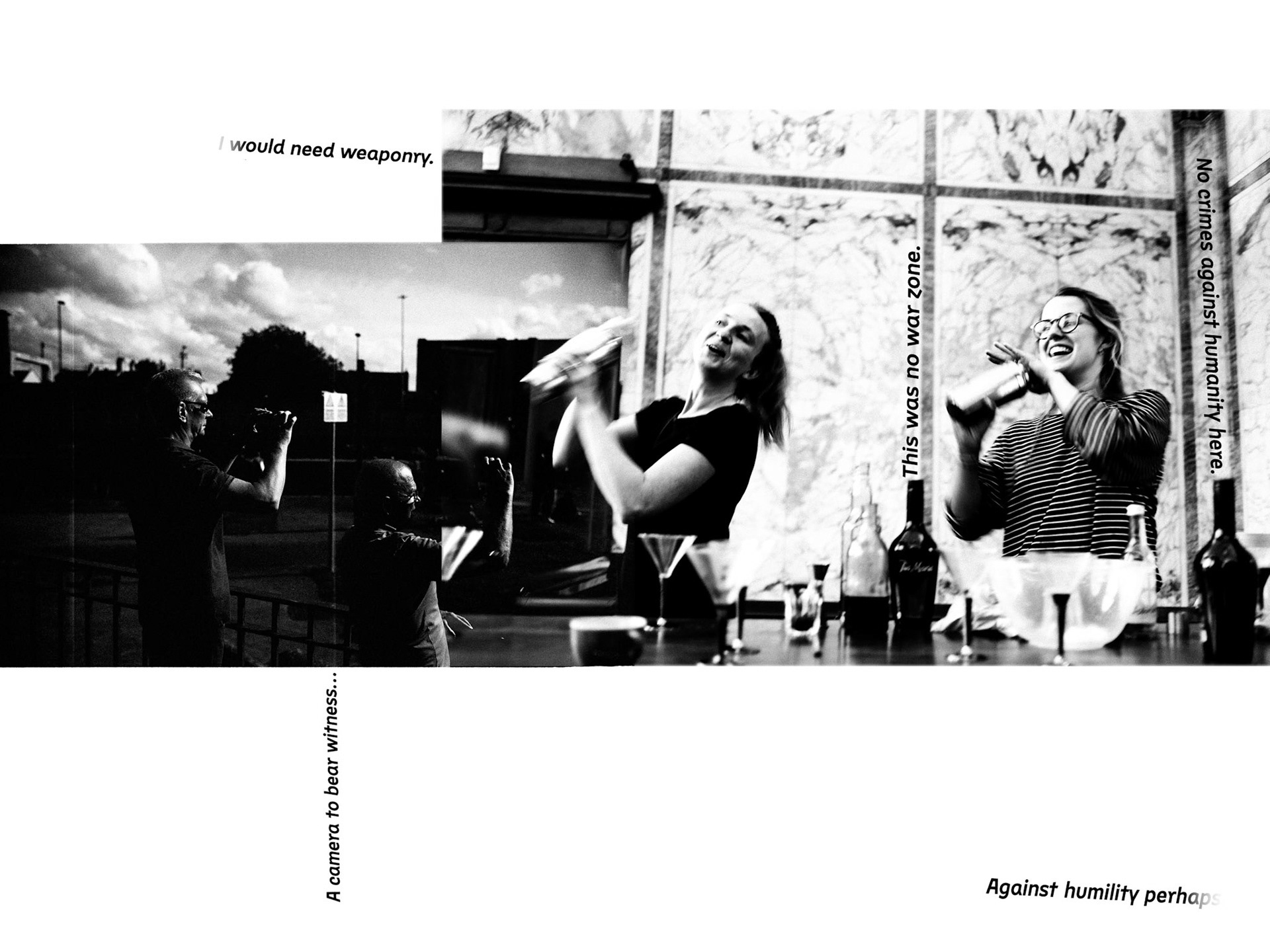

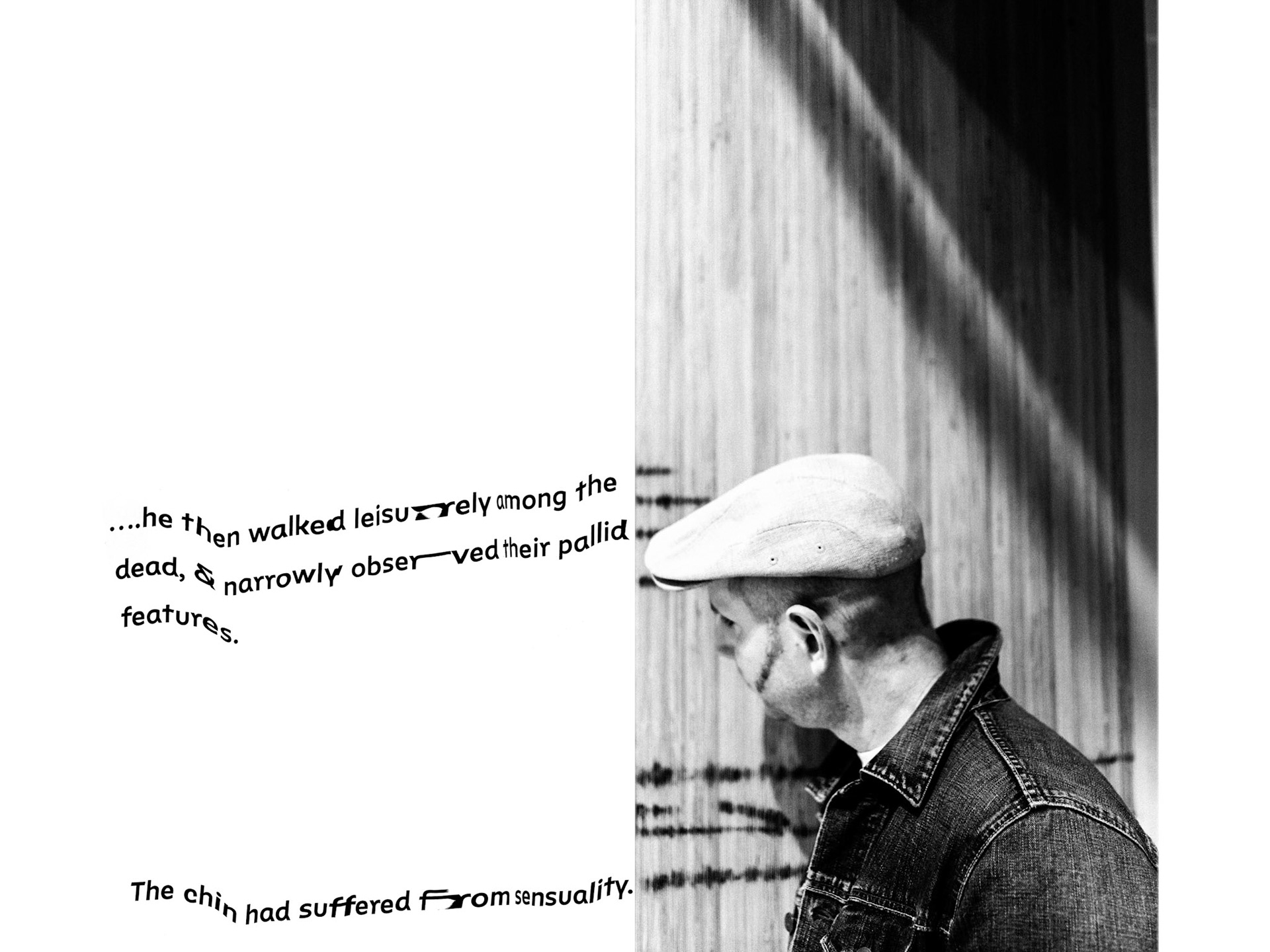

Then I got out my photographic comfort zone and began writing new chapters to continue the book. Three of these chapters also describe visits to the cave by people on their way to the afterlife. They also recount their life experiences for the education of the girl as Wollstonecraft had originally envisaged. My first visitor is someone new to the city but struggling to fit in. Faced with streets full of people wearing headphones and staring at their screens, he disconnects and eventually take his own life. The next character also suffers from a disconnection with society. This time through a lack of body confidence that results in the diversion of all her energy and resources to animals rather than other humans. These animals metamorphose into humans and attend her funeral. For my last visitor to Wollstonecraft’s ‘Cave of Knowledge’ I present a man so obsessed with music and gigs that his entire existence becomes defined by it. The final chapter I wrote describes the girl leaving the cave and moving to the city. She grows up and completes her education.

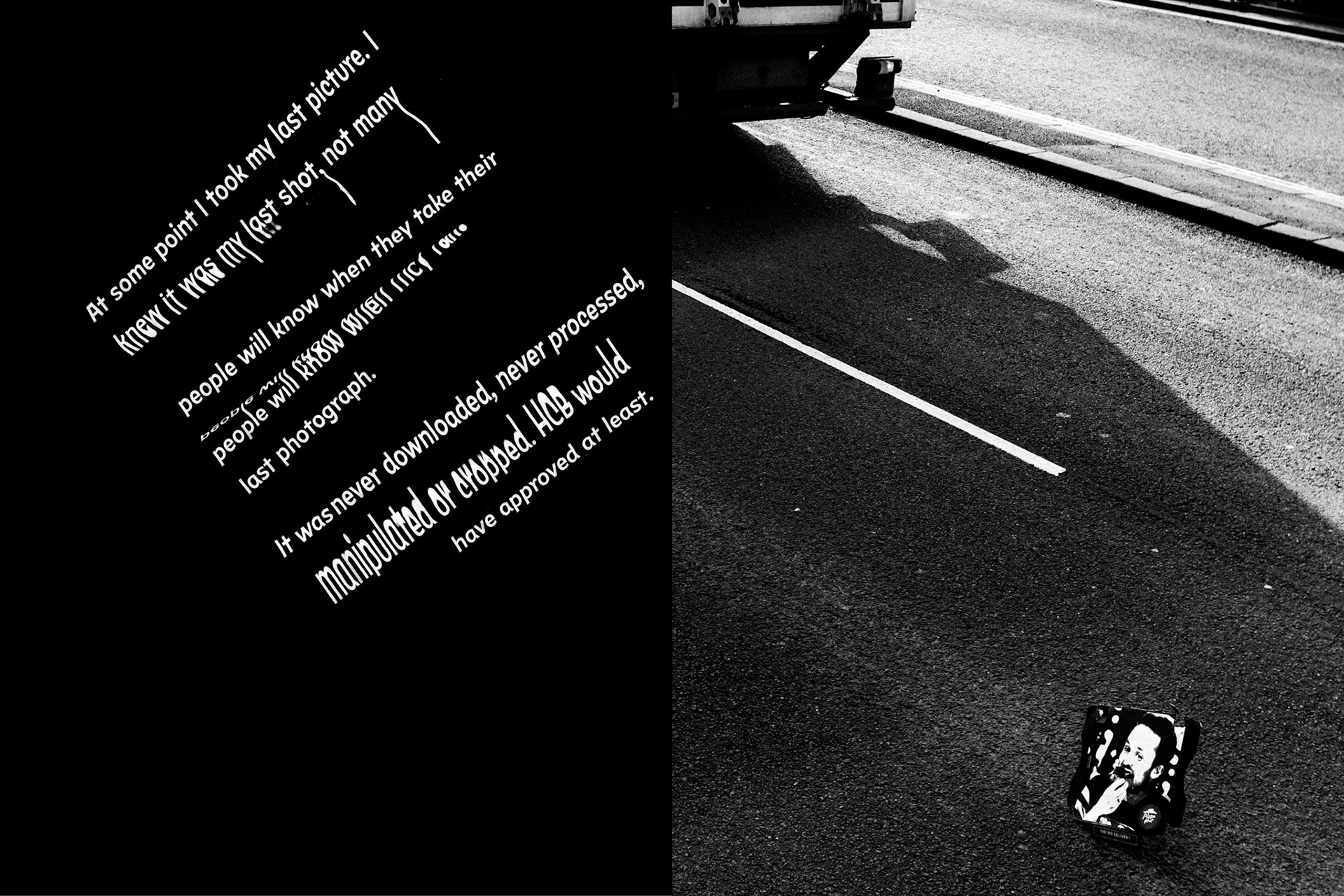

A sequence of images starts and ends the book but the rest is a graphic mixture of words and images. I did not use all Wollstonecraft’s existing text because my aim was that the images should not simply illustrate the text: they were to be an equal language in terms of the narrative. This ‘non-mimetic’ approach is different to many traditionally illustrated books that include images to simply illustrates, or mimic, a part of the text.

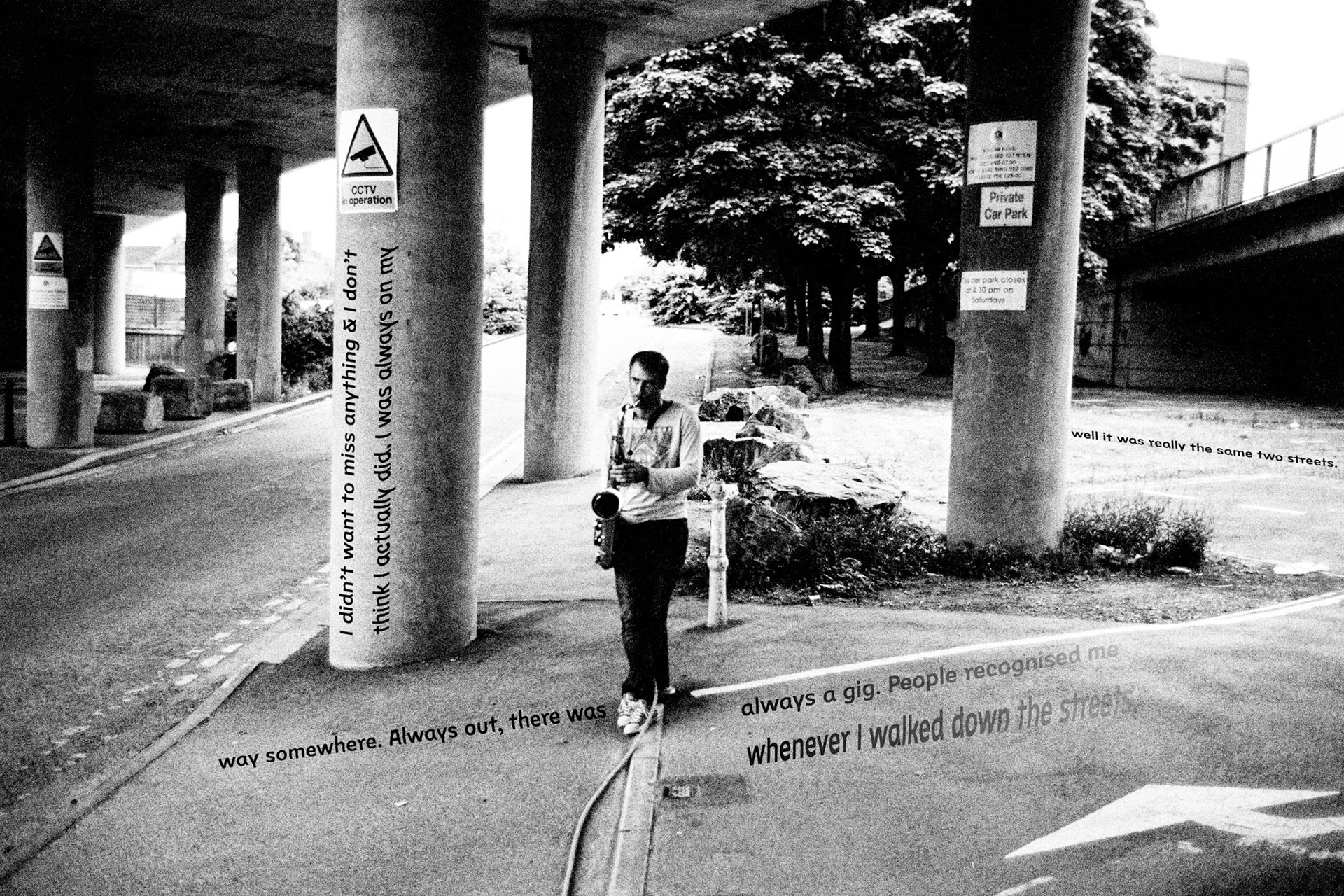

The unposed photographs were all taken in Bristol during 2016-2019 and hopefully they still retain a documentary value even without the text. As well as cropping, overlaying and sequencing the images, I experimented with the visual form of the text, manipulating it so it blends with the shapes and lines in the photographs. This design approach closes the structural gap between images & text with the goal of being easier to read as one form. Type is structurally contrasty and sharp, photographs usually not. Making the type softer through blurring and toning moves it structurally closer to the imagery.

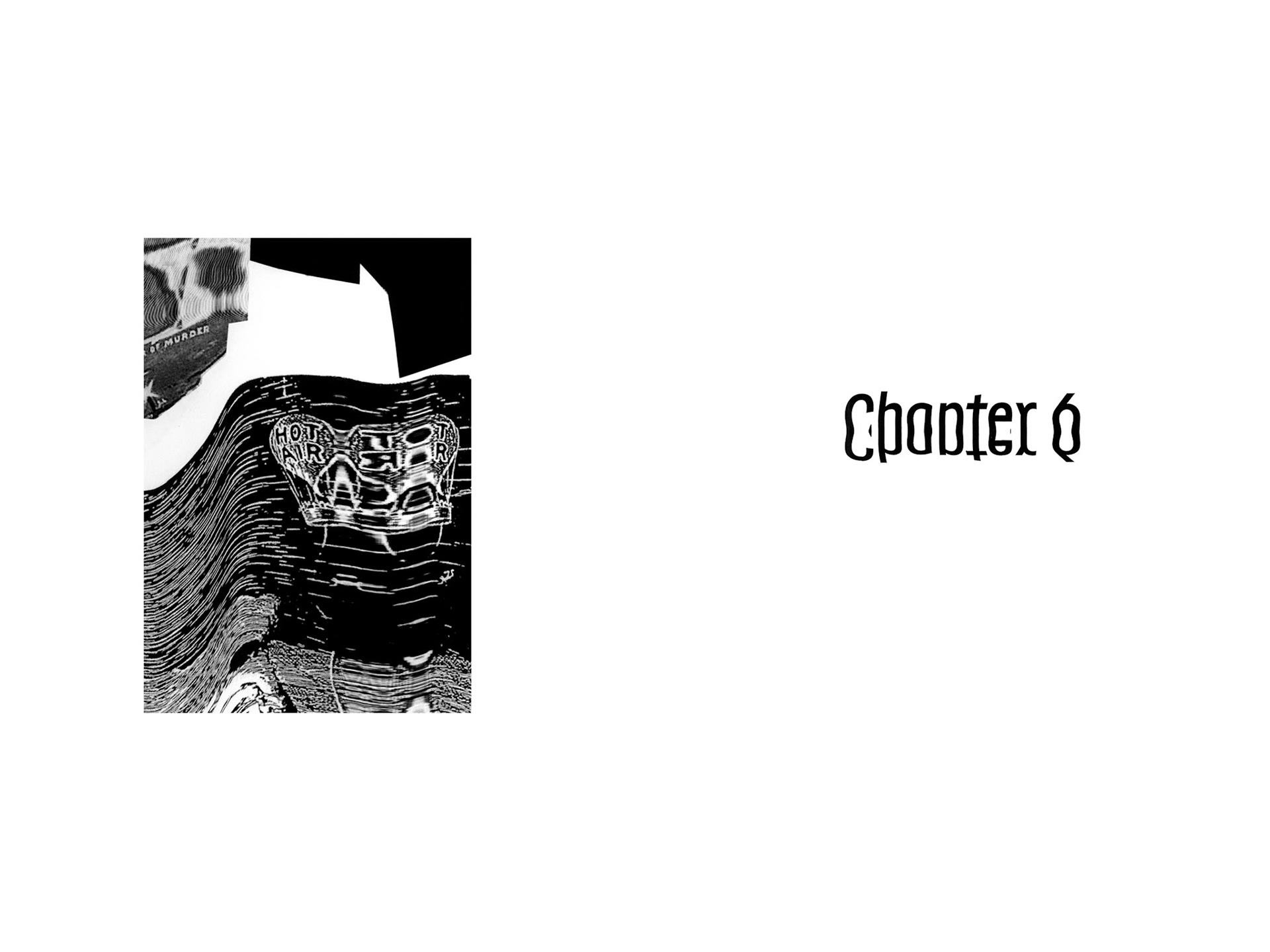

Emojis of the 2 main characters (the Sage and the girl) and the 2 main themes (education and death) were also introduced to help readers identify them in the narrative. Sometimes they replace actual words in the text. I felt some kind of additional visual key to the characters was important because my images of the various characters in the book are never actually of the same person twice. This is an inevitable limitation of using images of random people - as opposed to using models. The final graphic elements I introduced were collages. They define the start of each chapter and are based on 19th century maps of success in life.

The book is experimental. It is complex and no doubt difficult to read in places. Although it is intended as a work of fictional art, I was interested in the effectiveness of the design and conducted a small number of semistructured interviews using an advanced version of the book. As well as the ability of the design to communicate the story, I was also interested in seeing how people from different ages and reading backgrounds (i.e. primarily text, graphic novels or photobooks) would read it. The research results suggested that although the design could be frustrating at times, the extra effort and time required to decode a multi-modal narrative does result in a rich reading experience.

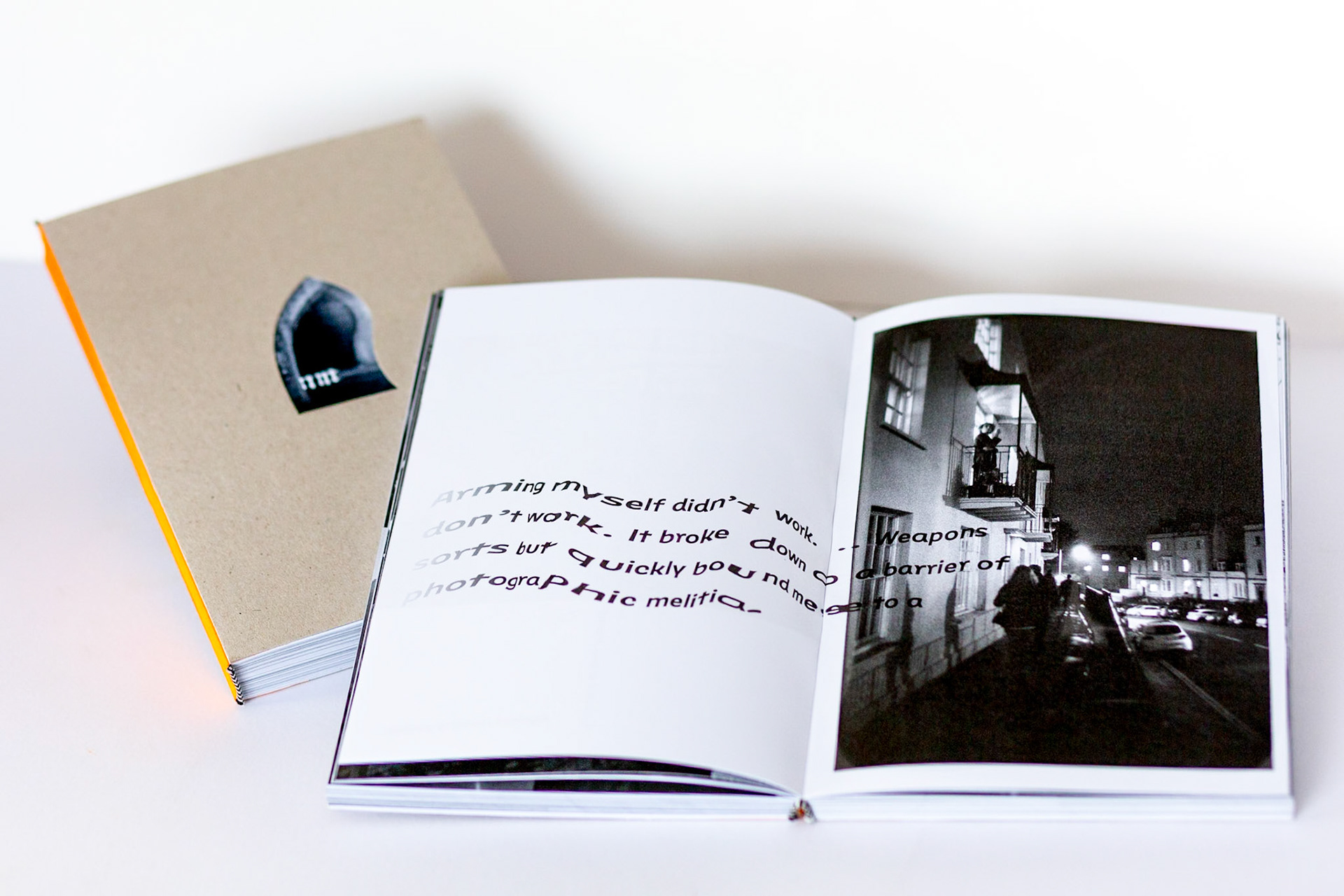

The book ended up being 360 pages in total and I have made 10 final maquette copies. They are all hand bound with glue and cloth, rather than stitched, to attain a flatter fold. This technique was also to aid the reading of the complex double page spreads. The size and portrait format of the book was designed to suggest it is just as much a piece of written fiction as it is a photobook or graphic novel.

It is all of these things Mary.

I have no idea which section of your bookshop you might find it in…

James Hudson, April 2020