‘Digital. Human. Migration: Newport’ is about the fictional migration of ‘digital’ humans. People whose value has been determined by a financial system that ranks their passports and the languages they speak. It explores migration, technology and aims to question how we value human beings. Narratives and ideas have been inspired by photography and zine making workshops I conducted with refugees and asylum seekers in Newport and Halifax.

Project trailer for social media. Click full screen icon at bottom right first for the best viewing experience.

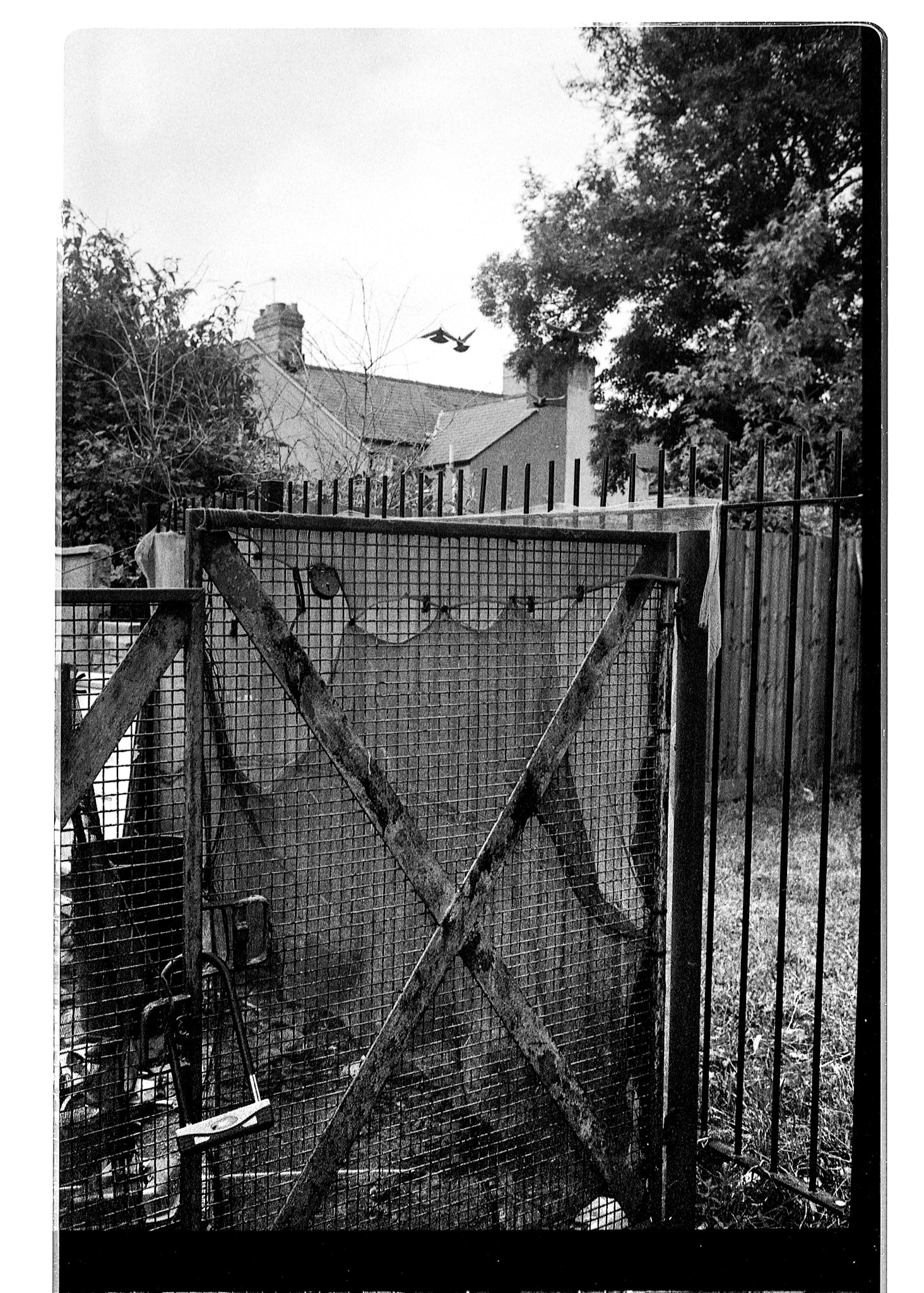

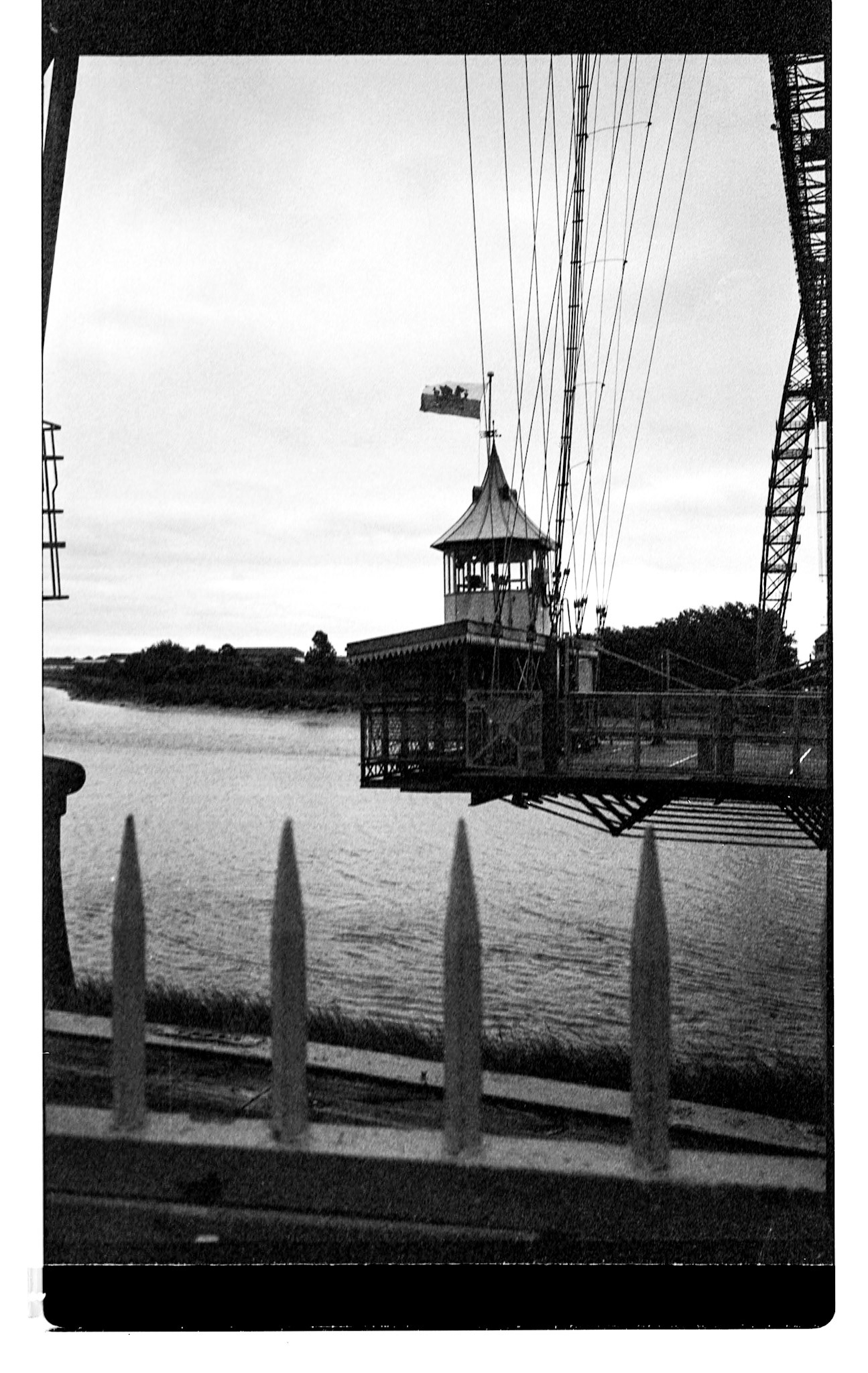

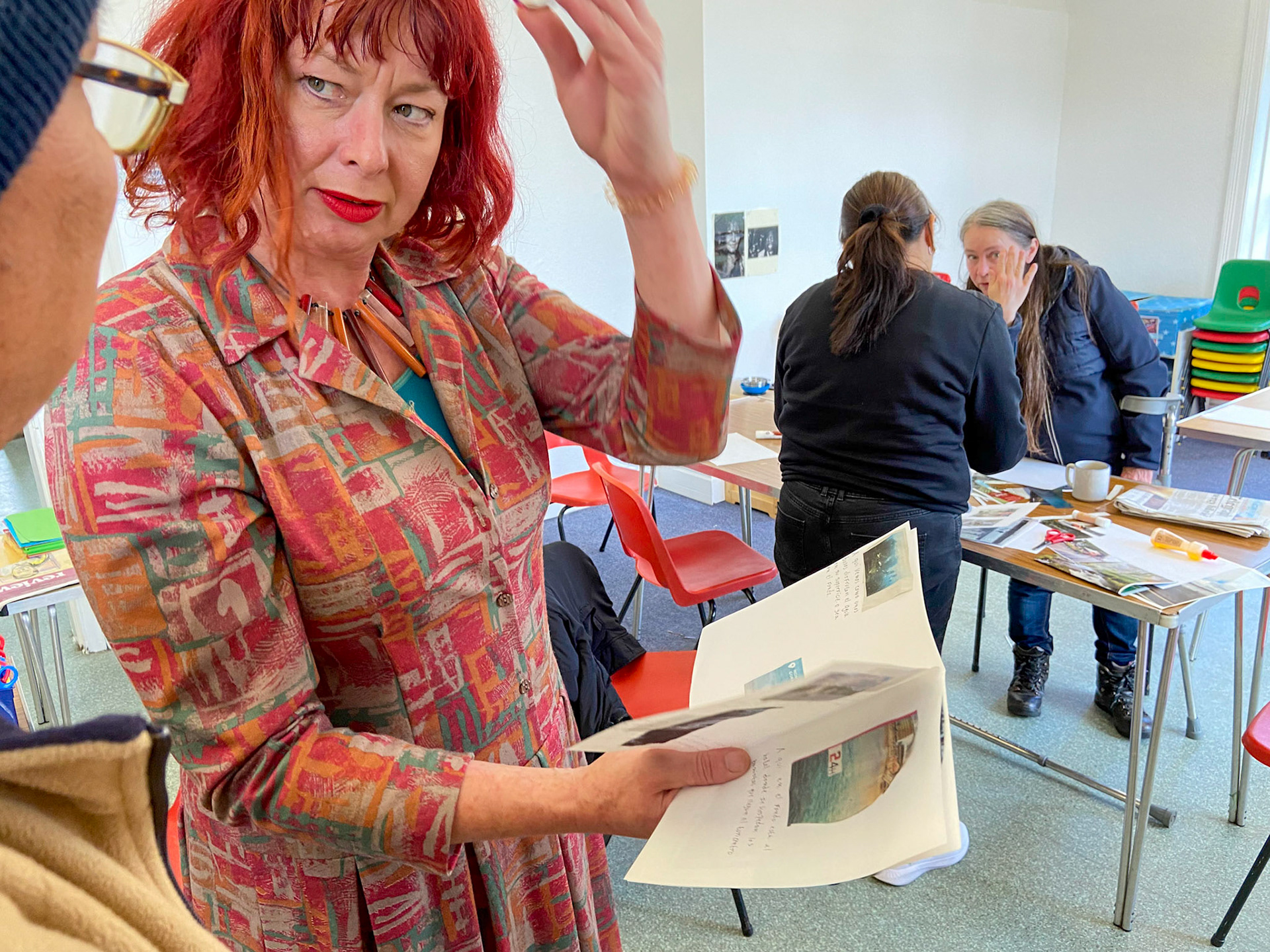

Workshop & Exhibition images:

Concept

The increasing ease with which we can transfer money round the world, compared to the increasing complexity of moving ourselves round the world, has concerned me for several years now. Freedom to travel should be a human right, but physical borders are closed for many people and even for those of us fortunate enough to regularly travel between countries it is getting harder not easier. However, systems for transferring money and goods (including art…) are opening up all the time and becoming easier and cheaper to access.

The recent pandemic forced many people to reconsider physical travel and also how ‘digital’ and connected they now feel. So, 2022 seemed like a good time for me to develop my own concerns into a piece of work that would explore migration, technology and our value as human beings.

I began to imagine a near future where physical travel had become so difficult that some kind of digital migration was the only option. A future where the only way to travel to another country is to physically convert yourself into data and then be transferred electronically. The value of your passport and the language(s) you speak determine your ‘exchange rate’ and therefore how you are valued by the system. Could you be traded whilst in the system?

As with most of my current projects, the work would be mixture of original photography, text and collage. It would be based in ‘reality’ by using un-posed photographs alongside texts inspired by real people I meet. For this project that inspiration would come from refugees, asylum seekers and other migrants who have travelled here.

The concept might be (science) fiction but our passports are already valued by a ‘mobility’ score based on the number of visas they include: a UK passport has 98 and an Afghan passport 3. Developments in crypto-currency and block-chain systems, plus the theory of quantum entanglement, have also now made the idea of ‘transferring yourself as money’ seem not such a leap of the imagination. Cities are also valued and ranked in a global financial index. London is No 2, Newport in Wales is not listed in the top 116.

The close proximity of Newport and having contacts there working with refugees, helped make it the ideal setting for the first chapter of ‘Digital. Human. Migration.’

Research

Finding out that our current passports already have a visa free score (VFS) that ranks them in terms of value, was one of the things that helped galvanise my original idea. Soon afterwards I found out that our cities are also already ranked in a list of financial centres.

I have yet to find a list ranking the most valuable languages, but I don’t doubt that it exists. It seems logical that a language related to the passport you hold and/or that is spoken in the city/country you wish to migrate to, would also have a quantifiable value.

Originally the calculation used to value human beings by the online traders in my piece of fiction was to be based on the migrant’s passport, languages spoken and the ranking of the place they were transferring to. In the final narrative I also added education, age, sex and colour to the calculation. I think of myself as an optimist, but ageism, sexism and racism are still alive and well in my near future dystopia.

The story was always going to be science fiction but I also wanted the technology behind the digital transfers/teleportations to be based on current theories and existing networks. Existing research in Quantum Entanglement provided me with enough information to develop the fictional science for my story. Quantum Entanglement is “A bizarre, counterintuitive phenomenon that explains how two subatomic particles can be intimately linked to each other even if separated by billions of light-years of space. Despite their vast separation, a change induced in one will affect the other” (quote taken from space.com, way more succinct than anything I managed...).

One of the major problems in transferring the subatomic particles of a human is the complexity (temperature fluctuations and neurons firing in the brain for starters), of a living human being. In my narrative, the body is teleported when dead and the living conscience of the migrant transferred digitally. To keep the data ‘alive’ they are transferred as NFT’s (Non-Fungible Tokens – currently used to trade digital art) and through an existing banking system network. Hopefully this gives the story a more believable background for the problem that arises in the story: human data is traded on route to being re-patriated with the physical body it had been taken from.

I had the basis of the dystopian technology worked out, but still needed inspiration for a specific personal story for this first Newport chapter. Originally, I had spoken to The Gap Centre in Newport and St Augustines’ Centre in Halifax about sitting down with some of their refugees and discussing their journeys here to the UK. Not to use those stories as journalism with real names and places etc, but purely for inspiration. However, the more we discussed how this process could work, the more difficult and riskier the idea of interviews became. Even though both these centres often work with the same refugees and asylum seekers they don’t know the individual details of how they physically got to the UK. For many it was a traumatic experience. Interviewing them, no matter how casually and well meaning, may induce trauma and that was not something we could risk. I would have to come up with another approach.

Just being around some of the refugees and asylum seekers at the Gap Centre and St Augustines during initial visits was already starting to inspire me though. The more time I spent there the more ideas came up. So, we decided that I should run workshops instead of interviews, create an informal atmosphere where they could talk if they wanted to, but I would still not ask them about their journey here. This approach was much better from a public funding point of view as the participants would get to meet other refugees and asylum seekers, make work and be involved in an exhibition.

Workshops

A few months before the first photography workshop I led in Newport for this project, I attended one myself as a punter. And with hindsight this was a good thing. It reminded me why people go on workshops; learn new things and meet new people. Learn new people and meet new things even… Why wouldn’t you go on a workshop! What is there to lose? An hour of your life when you don’t meet anyone new and don’t learn anything new at all… possible. But highly unlikely.

The Gap Centre promoted the photography workshops to their refugees and asylum seekers, and one Monday in June we all met up in Newport to begin the first one of four. We met up at most photographers’ worst time of day; 2pm with the sun directly over our heads. But a great time of day for meeting new people and learning new things; straight after lunch and before any of the obligations that pile up as the afternoon becomes evening.

I had done some preparation of course, but I didn’t know how many would turn up, what languages they would speak and what their knowledge and enthusiasm for photography would be. So, I didn’t want to have an exact plan. In the end there were eight of us and there were nearly as many languages spoken between us. All had smart phones and almost all with enough battery and memory for an hour’s worth of new photos. After the introductions we started walking in no particular direction. I tried to let them lead the way, interested in what they saw, what they wanted to photograph. A rather grand flowerbed was the first object to stop us. Even something as every day as this can immediately divide us visually. Should you concentrate on one flower, or frame a small group of them or take a step back and show the whole thing in its context? What did you see first, how you want to remember it, what do you want to show the world… I suggested subjects, offered options on angles they might not have considered and reviewed their work as we walked. Most photos we take really aren’t that good, but the more we look and work at it, the greater the chances of creating good images. You know, the ones that can hold our eye for a couple of seconds, rather than less than just one second.

Most of the group to wanted to show a positive, colourful view of Newport. And there is plenty of that to show. Personally, I see beauty in decay (‘a penchant for the gothic pervades me’ as I one wrote on a dating app bio resulting in no matches…) but showing damage and mess is often read purely as criticism of a place. Newport is the sort of place where you can easily do that as well.

The following three workshops had similar attendance and vibe. Some did all four, some just one. But our group generally veered towards the colourful and positive. Flowers, sculpture, murals. Photos of each other and of themselves. Smiling. Posing. Shots of the city, their new city. Their temporary home, perhaps a home forever.

As well as the Newport photography workshops, I also did a zine/booklet making workshop in Halifax at the St Augustines centre. It was part of their ongoing series of arts workshops. Their existing theme of ‘water’ fitted in quite nicely with my migration theme, after all, we are an island. Having introduced myself and my practice, we started looking through magazines and cutting out any images that resonated. Next stage was to begin to lay them out, see if any relationships developed between them, and also if certain words (either cut out from magazines, or just written down) wanted to join in. Little narratives started to develop. Next, we folded up some A4 sheets of paper and stuck the images and words into them using white space when we needed the sequence to breath. It was a short workshop and most of the students had not made zines before, but I was super happy with the outcomes. Some really great juxtapositions and sequences. More than one of the students adding text and creating little story books.

Photography

When it comes to the photography, I tend to jump the gun a bit. Before partners are in place and before funding is approved, photos have usually already been taken. These first images are often never be used, but sometimes they come to define the project. Taken before pressure and structure is imposed; raw, visual responses to a half formed idea.

Some of the early images I shot for Digital. Human. Migration (before funding was agreed for this first Newport chapter) were taken in the City of London and, although I decided only to use images taken in Newport for the project, they did influence the narrative. A photo taken outside the museum of the Bank of England that shows a poster with the text “See Money come to life” right next to a big cross in the design of the old door the poster was placed next to. To me the cross signifies ‘No Entry’ and would be a graphic I was drawn back to again and again. The text in that poster is also a kind of summary of the written narrative I developed later on about people being turned into tradable data and then brought back to physical life.

I spent a couple of days wandering in Newport looking for graphics (an electric car charging graphic that, when placed upside down, looks like a human face being plugged in) for action (the boy with a Lightsabre playing in the street - a magic wand, a wave of which could teleport you to another place) and for text (the shop front with the words life, money and bitcoin). The workshops yielded a couple of images as well. The shot of the shirt with the words “Here now There then” was taken inside The Gap refugee centre.

On the way back to my car one day, I noticed a discarded suitcase that had failed to attract my attention when I had first walked past it earlier. It now suggested arrivals and departures - key parts of the story - but obviously I wasn’t in tune with that when I walked past it the first time. But now, having been out photographing for hours, I was ‘in the zone’ and much more visually alert and receptive. Hold a camera in front of your eyes long enough and maybe it starts to filter you.

Writing

I was concerned about how inspiring the workshop approach might be for narrative ideas, but it turned outjust being around people at the Gap Centre and St Augustines during my initial visits was already starting to inspire me.

During the workshops, some talked unprompted and some even showed me images on their phones of the countries they had left behind. But most did not talk much, happy to walk, photograph and make things. It was enough. The characters and story line started to form.

The quantum entanglement research and contact sheets of images I had taken were the other ingredients for the story. These elements all influenced each other and the process of swapping text for images and developing the pseudo-science continued right up until the booklet went to print. The writing evolved into two distinct voices; a narrator discussing the teleportation system at the beginning and the voice of a migrant who went through the system. This character doesn’t know why it took so long, and where he was for six months. The narrator returns at the end to fill in more of the story, details the main character is still unaware of.

The character is inspired by several of the refugees and a random person I saw on the streets of Newport. The recent news story about the guy who threw away a hard drive containing bitcoin (now) worth hundreds of thousands of pounds also influenced the story - he had been asking the council to help him look for it in the tip.

Whilst researching roman gods for another project, I came across a description of the god Janus that resonated well with the voice of my narrator. So, my narrator became a god – the god of doorways, of beginnings and ends. My characters journey begins in January, the month whose name developed from the word Janus.

In many ways this is my favourite part, but it is also the hardest and most frustrating. It never feels 100% resolved because the relationship between words and images is complex and can be contradictory. The way you present these two (sometimes unfriendly…) media together almost always alters their individual reading.

But this is a process that really interests me and is now at the heart of my practice.

The process started with my contact sheets from Newport. As quickly as possible – and without thinking too much – I looked through them and marked anything that stood out. These images were then printed out on normal laser printer paper and stuck on a magnet board in a random order. I then left them alone to talk to each other for a few days. Like locking the door on a room full of people who have beef and need to get it sorted out...

Later I started to move the images around, grouping them in themes, pairing them up and putting them in mini sequences.

The images soon fell into the following sections; The desired destination, The government/private company’s offer, The teleportation/digital transfer and The arrival.

Plenty of the images showed barriers, crosses, fences etc. Images that say ‘No Entry’. There were also several images showing texts with common words: “This way for travel money”, “Life. Cash Machine Money Bitcoin Here” and “Here Now There Then”. I did get a little bit excited when I spotted this…

The whole sequence starts with an image of the back of a very white hand and ends with the back of another very black one. A subtle visual connection, perhaps one people won’t notice consciously. But you know it’s there now.

Exhibition

The small exhibition in Newport was never intended to be the final, or most important outcome of the project. It was a vital element in presenting the refugee and asylum seekers work and getting my work-in-progress up onto a large wall – a process I find really useful in the production of any sequenced body of work.

We switched the location from an empty shop in the centre of Newport to a nearby community centre called ‘The Place’. A colourful, accessible building with a café, a sitting room, artist studios and an exhibition performance space called…. ‘The Space’.

The refugee/asylum seeker students work would be on one wall and my work-in-progress on another wall. In The Space, at The Place.

I did an initial edit, and then some basic cropping etc on the students’ images. They were printed out on a standard laser printer and some of the students came to help arrange and hang them on the wall. We laid them all out on two large tables in front of the wall in The Space, at The Place and began shuffling them round. Eventually we achieved an overall balance of colour and shape in the layout and had included at least one shot from each of the students. About half the workshop participants submitted images for exhibition.

At about 5pm on that Monday we laid out the snacks and soft drinks - taking almost no account of their shape, size or colour and how well they sat next to the other snacks and soft drinks. Information sheets about the project in both Welsh and English were also put up around the gallery, even remembered to put a set low down for wheelchair users.

Many of the refugees and asylum seekers from the Gap Centre (located close by) then came down, some with their host families, their partners and children. Photos were taken of the display, of them in front of the work and even of me, with them. One of the students was given flowers by her host family. A proper exhibition ritual. I was genuinely touched by the effect this very modest show was obviously having on the participants.

One of the asylum seekers started playing the public piano at The Place that day too. He was really good. Since coming to Newport he hadn’t had the opportunity to play but now, having found an accessible piano via his involvement in the show, he goes back to play there regularly.

Once the rough sequence of images had been shuffled around on my studio wall for a while, I recreated the sequence on screen using Lightroom®. There was more tweaking of the sequence and then they were exported as individual files and placed into a new file in the page layout software InDesign®. It became fairly obvious which images should be intense as full or double page spreads and which needed some white space round them in which to breathe and slow things down.

The written narrative was by this point clearly in three separate blocks, and therefore relatively easy to place it equally between these four groups of images. At this stage there was still plenty of rewriting to do. It’s only when I see a printed-out maquette of the booklet that I can see how the text is behaving. It reads slightly differently surrounded by the images than when it was all alone in a Word file.

The text is three different accounts of the same situation, so I did initially experiment with different fonts for each block of text. I didn’t want the typography to overawe the sequence of images and the text so the design was always going to be subtle. The columns of text increasing tilt to the right just slightly to suggest all might not be ok.

An inverted crop of the image used on the cover – the side of a van with a ‘network’ illustration that is comprised of lots of crosses, the cross graphic (that signifies ‘no entry’) being repeated in several of the other images and is also used faintly on the white pages to help visually close the gap between images and text.

Inverted video grabs also run through the entire booklet getting gradually bigger. A little visual sub plot. This idea came to me when putting the work-in-progress on the wall for the exhibition. Big square frames differentiate those images from the rest of the narrative.

The text at the beginning of the booklet is actually a quote. It was perfect as the voice of the narrator (the god Janus) introducing himself. So it is placed quite big across two pages rather than small and discreet as quotes often are at the start of books. I haven’t stolen the quote (it is credited at the back), I’m just borrowing it.

For sharing the progress of the zine/booklet artwork with my peers, I used inDesign’s own online publishing option for the first time. I call it an option but I bet Adobe (the company who make it) call it a ‘solution’. It was pretty good. So, after the file had been sent to print, I began experimenting with its animation options. The aim was to create a permanent online version of this Newport chapter, something I have not done with any of my previous projects.

The tools are quite basic (fades, fly-ins etc) so trying to get the balance between subtle movements that enhance the reading experience but don’t jar with the theme, was tricky. Really did not want it to end up looking like a PowerPoint presentation…

I added slight movements in the blocks of text. Some of the images of the guy with the dog tags, that run through the booklet, disappear from the screen after a few seconds. These movements aim to increase the unease already suggested by the images and text. I’m looking forward to feedback on this online version. Will certainly be making them on all future projects - and perhaps some of the old work too.

I love the physical nature of paper booklets - the skate/bmx zines and magazines I made in my teens and early 20’s having galvanised that love - but I have also been regularly flirting with digital publishing over the decades since then. It is a love/hate relationship with digital and I’ve never fully embraced it. I know it is hugely accessible and democratic, but the time it takes to create really good, engaging digital content must not be underestimated. And all that time – the making and the watching – is while you are sat on your arse in front of a screen. Like we all are right now. Also, I’m not that good at making it... But Zach Evans is, so I got him involved in making a short trailer that promotes the work. It poses the question: If you were digitised, what would you be worth?

This is the first directly funded public/lottery money project I have done. It was also the first I have done that involved working directly with members of the public. These two ‘firsts’ are related, they were inseparable.

I would not have been able to make the work without the involvement of other people and, even if I could have funded it myself, I don’t now believe it would have been as resolved. We can do research at home on the computer, all the info is out there – inspiration, technical info - and we can make work at home and even now have the means to publish it: “all from the comfort of your own home!” as someone said when the concept was still new… Comfort is the problem word here.

Walking round Newport with refugees and asylum seekers I knew nothing about – and perhaps would have been quite upset/angry if I did know everything about – encouraging them to take better photographs with their smart phones was not, initially at least, comfortable. I was concerned about what they would get out of it, I was concerned about what I would get out of it. And this mattered because it was tax payers (and gamblers..) money that was paying for it. I’m trying to be a visual artist - to explore and present ideas -I don’t consider myself a social worker…

But, maybe, I am. Or at least partly.. Because art, with a big ‘A’, is a form of social work. This project has pushed me over the imposter syndrome hedge. It has put me into a field where other artists are coming up with ideas and getting on with making things without the baggage of worrying about if what they do is valid, or whether they should be doing it, or hasn’t someone else done it before or, or, or…

Working with the public and having to justify your actions in detail gives you agency as an artist. It gives you confidence.

It has been a great experience and I’m really happy with the printed outcome which is just the first chapter of a larger body of work I will be pursuing over the next few years in other cities.

The stage has been set. The concept and pseudo-science in place. Other migrant stories set in other cities can now be fed into this fictional framework.

James Hudson, October 2022